If you live in a desert region you typically have at least three obstacles to overcome when it comes to growing your own food: not enough rainfall, too much heat, and/or poor soil.

Water

The obvious answer to a lack of rainfall is to just water your garden yourself. If you have to do this manually, it can add a lot time and effort to your garden. Sprinklers and/or drip irrigation has upfront costs, but both greatly reduce the amount of time you have to spend working on your garden (and time is money, after all).

Of course, that’s all well and good if you have an affordable source of water, but some people do not. I have seen people buy very affordable pieces of land far from any municipal water source, and they do not have the money to dig a well just yet. Such people may get water delivered for their household use, but they have to be sparing with it because of the expense. Getting and storing water just for a garden may be out of their budget.

In other cases, people may have a well, but as a lot of the deep aquifers in the Western U.S. are drying up, they may not be able to pump enough water to supply their garden as well as their own needs.

And even if you do have access to city water, the cost of it may be prohibitively expensive for watering a garden, or you may be restricted in how much you can use and when (especially for outdoor uses), leaving your plants underwatered and underproducing.

Recycling Graywater

Graywater is water which is not safe to drink, but not particularly dangerous either. This is water from kitchen and bathroom sinks, tubs/showers, and washing machines and dishwashers. (Blackwater, by contrast, is water from a toilet, which is considered dangerous because of pathogens and parasites present in fecal matter, and it must be sequestered in a septic tank.)

Every household produces a lot of graywater on a daily basis. This graywater can be redirected from a septic system, traditional grease trap, or field line and run through a reed bed to be cleaned to the point that it’s safe to use on plants.

Reed beds can be build directly into the soil, like ornamental ponds, or they can be created in a large container, like an IBC tote cut in half, or even an old bathtub. How many you need will depend on the number of people (i.e. the amount of water you’re using) in your house and how dirty your graywater is. As one YouTuber put it, it’s really just trial and error; whatever method you use, make it easy to expand it if your water is not coming out clear enough at the end or you’re overwhelming the system with the amount of water you’re putting out.

You can use more ecologically-friendly soaps and washing powders that are safe to place onto plants, but all soap is alkaline, so you’re still going to want to filter it, at least a bit, to make its alkalinity closer to neutral. Alternatively, you can deep-water fruit trees with your graywater, allowing the soil to do the filtering work. This is a bit more work and expense on the front end, and it doesn’t water your annual vegetables (their roots aren’t as deep as trees or perennial vegetables), but once installed, it’s pretty much maintenance-free.

This video covers some plumbing considerations when converting to graywater recycling:

For kitchen sinks, which produce more grease and solids (think food particles), some people empty their drains into a worm bed first, letting the worms take care of the solids that can clog a reed bed, and then they let the reed bed clean the water. (Worm beds are also a good place to put your kitchen scraps; I have a pair of worm boxes in my house and they process my food waste and old, spent dirt and turn it into fresh, nutrient-rich dirt that I use to pot plants.)

Rainwater Harvesting

In some desert environments, it does rain, but it comes in large amounts, all at once, and then it doesn’t rain again for a long period of time. When there are large deluges like this on very dry soil, the water has a tendency to run off the soil and end up flowing into a nearby wadi and leaving. Very little rain actually soaks into the soil where it is needed and the garden will be dry again the next day.

Swales are intentionally-made dips or shallow ditches that catch water as it runs downhill or across a piece of land. These little depressions hold rainwater until the soil can soak it in, correcting the issue of rain today, drought tomorrow.

On flat desert land, people dig large, bowl-shaped swales (these are also known as “zai” in Burkina Faso, where they are a traditional farming technique near the Sahara Desert), 2-6 inches deep and 6-20 inches across (depending on how many plants you want to put in it), and plant a perennial fruit tree or large bush in the middle, surrounded by annual plants. (Think of a raised bed in reverse; these are sunken beds.) When the rains come, the rain flowing across the property ends up in these shallow catch basins and stays, keeping the plants there watered for quite some time.

Swale ditches are also great alongside hard surfaces, like a patio or driveway; plant in these ditches and any rain that hits the surface will run off into these plantings.

Another desert rainwater harvesting technique is to use rocks to build short walls, dividing up large plots of land into smaller plots, more along the size of a backyard garden. These rocks—which can be used in conjunction with a swale—also stop water from rushing over the property, reducing damage to plants and washing out of mulch in heavy rains, and re-directing the water into swales and zai pits where it can soak in.

Fog/Dew Fences and Rock Water

Mulch is a critical part of a desert garden. Woodchip mulch absorbs moisture, like a sponge, making water available for plant roots long after the rain or irrigation stops. But any kind of mulch prevents evaporation of water from the soil, keeping your soil from drying out so quickly.

While there are a lot of benefits to woodchip mulch, like holding onto moisture and improving soil quality as it slowly rots, desert gardens may actually derive more benefit from rock mulch than woodchips. Woodchips work well where rain comes in large, but infrequent downpours. Rock mulch works well in areas where there is less rainfall, but there is a large swing in temperature difference between night and day. This is because the rocks absorb heat during the day, and when the air temperature cools rapidly at night, the large temperature difference between the rocks and the air creates condensation. (This is the same principle, but in reverse, when your glass of ice water sweats in a warm room.) This condensation rolls off the rocks and onto the soil underneath it—rock water, if you will.

Some desert cultures used rock walls in their gardens to shade plants from strong western/southern sun, protect plants from strong, blistering winds, and to create a larger surface for collecting condensation. (This is known as the Talus Garland Effect.)

Working on the same principal, but very different in construction, is a fog/dew fence. Fog fences have been used in the high deserts of the Andes Mountains where moisture from the Pacific hits the mountains and stops. Fog manages to get across the mountains, but rain clouds rarely do. Very tall fences made of mesh “catch” the fog, like a spiderweb covered in morning dew, and the water trickles down the mesh and into what is essentially a rain gutter underneath it. Piping carries the water from the gutters down to villages on the hillsides below.

But you don’t need fog to capture water from the air. Tests in the Middle East found that the same mesh fences will capture dew—just like the spiderweb—and in amounts to make it worthwhile.

While fog/dew fences have primarily been about providing remote villages with drinking water, they can just as easily be used in a garden to water it. They can do double duty in a desert garden by helping provide shade and a wind break for your plants during the day, and at night any water that is captured can be piped out to the plants with drip irrigation.

While the previous video is an example of large-scale fog fences to capture water enough for a village or large farm, this is a video on making one more on the scale of a backyard. The creator found an HVAC air filter increased surface area and therefore water catchment, but you can use window screening if that’s easier to find or you want to scale up the size of your panels.

Saltwater

Another problem that people in desert regions may face is salty groundwater. There are Dutch researchers who have been testing crops with seawater to see how much saltwater different crops can withstand, and to try to create varieties through selective breeding which are more salt-tolerant than current options. So far, they have had good success with root vegetables, especially potatoes, tolerating seawater. Yield is reduced, but several varieties produce enough to still make the effort worthwhile. Israeli farmers in the Negev Desert have also been watering plants—on an industrial scale—with their region’s saline water.

So, if you have salty soil and/or groundwater, don’t despair. It will take more time and effort, but through trial and error, you can also discover varieties that will tolerate your conditions, and saving the seed from the best plants will slowly make your garden more and more productive.

If salty groundwater is your issue, you can filter some of the salt out the same way a reedbed can filter graywater: instead of using freshwater reeds, use coastal plants that tolerate a lot of salinity.

Before the Greening the Desert Project (more on that below), Geoff Lawton did a government-funded permaculture trial on agricultural land in Jordan. There, salty groundwater ruined productive land, but he proved that his permaculture design (which involves a lot of woodchips) was able to negate the effects of the salt water, allowing plants to thrive without concentrating salt in the soil.

Irrigation

Drip Irrigation

A source of water only solves half your problem; you still need to get the water to the plants. If water is a precious commodity due to its scarcity or cost, then you don’t want to waste any of it watering weeds, walkways, and other unused areas, as happens when you use sprinklers or a water hose. Soaker hoses are often touted as an easy and fairly cheap way to irrigate gardens and landscaping, but the #1 complaint about them is more water flows out close to the faucet and less at the end of the hose. You can take this into consideration when designing your garden, putting heavy drinkers, like tomatoes and peppers close to the spigot and more drought-tolerant plants, like Mediterranean herbs, further down the hose, but not every garden has the luxury of being laid out this specifically. What’s more, some water is still wasted on the ground in between plants.

Drip irrigation, invented in Israel to water crops in their desert environments, reduces water waste almost entirely. With it, plants are laid out with precise spacing and little joints in the irrigation pipe, situated right next to the stem of the plant, drip water from a tiny hole. Not one drop of water is put anywhere other than at the base of every plant, and a plastic cover over garden row keeps the water from evaporating and weeds from stealing the precious water.

There are drip irrigation kits that you can buy, but if you can’t afford one, try a cheap water hose (make sure to cap the end) with pin-pricks made in it where your plants are. Remember, you want a drip, like a leaky faucet, not a spray.

Using captured rainwater? Water pressure isn’t a problem. Elevate a food-grade 55-gallon drum (aka pickle barrel) next to your garden and connect it to your irrigation. Fill the barrel with water and open the spigot. (Instructions: https://theownerbuildernetwork.co/easy-diy-projects/easy-to-build-rain-barrel-system/)

Another benefit to this sort of reserve-water system is if you need to be away from home for a few days, you can fill the barrels and leave the spigot open. You may waste some water by watering more than is necessary, but it’s a much safer alternative than leaving a house spigot on and walking away from it for days. A hose failure in such a situation would lead to a catastrophic water bill, not to mention flooding your garden.

Ollas

A more ancient technique for watering is an olla. An olla is a bulbous vase of unglazed terracotta that is buried in the ground and then plants are planted around it. The terracotta slowly weeps water into dry soil, but does not weep water when the soil is wet, so you cannot waste water by over-watering. And because it’s watering the roots of the plant, you don’t have to worry about water loss due to evaporation or mildew caused by wetting the plants’ leaves too often. How large an area the olla will water around itself depends on the size of the olla, but you can expect a foot or two of spread around an average-sized olla.

The drawbacks to an olla is that they have to be filled manually, so they don’t save a lot of time over hand-watering. (Although I did see one person who connected his ollas to runs of PVC, so he could fill all of them simultaneously, but he might as well have turned all that piping into drip irrigation and skipped the ollas.) They’re also prohibitively expensive if you’re planning on using more than just a few of them (and most gardens are going to need more than just a few), although I have seen people making cheaper versions using terracotta plant pots that they glue together top-to-top using silicone caulk (Instructions: https://sproutedgarden.com/how-to-make-diy-olla-pots/). Lastly, if you live someplace where the ground freezes in the winter, you will have to dig them up at the end of the season because freezing ground expands and can breaks the ollas if they’re left in.

All that being said, people have combined the idea of ollas with drip irrigation and have recycled plastic bottles to accomplish the same thing (either above ground or in it). Water will leak out of pinholes in a plastic bottle regardless of how wet the soil is, unlike an olla, which waters via a wicking action, but plastic bottles can be gotten in many ways for free, so that’s a plus. And even if you don’t want to try to water your entire garden with ollas (plastic ones or otherwise), they do work well for watering potted plants if you’re away from home for a few days.

An IV dripline and plastic bottles create cheap drip irrigation:

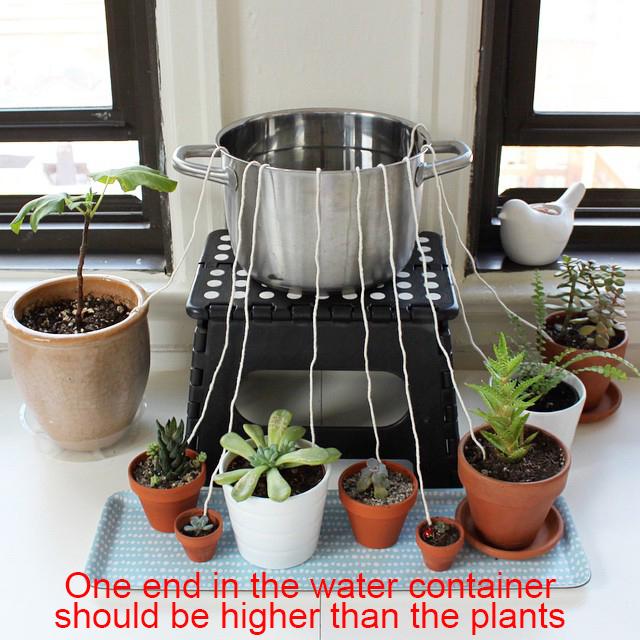

Wicking

Another root- or deep-watering method is wicking. On a small scale, fabric, like old towels or sheets, is cut into strip and is buried at the bottom of a pot or garden bed, leaving a tail hanging out. This tail end is put into an elevated container of water and the fabric will wick the water out of the container and along its length under the soil.

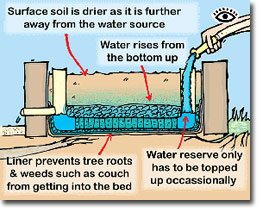

On a larger scale, containers (like an IBC tote cut in half) have a base of gravel and a pipe that fills this area. The soil itself wicks the water up from this underground reservoir which, when properly sized, only needs filling about once per week.

Heat & Sunlight

When seed packets say that a plant needs “full sun,” they’re basing that on northern latitudes (think Ohio or New York state). In the Southern states, like my home state of Tennessee, plants can actually get too much sunlight and suffer from “sunburn” on their leaves and overheating. This goes double for desert climates, like the Southwest. That’s why you have to ignore the instructions on seed packs and shade your plants from noon onwards.

Depending on the amount of heat you get, it may be sufficient to plant your tender annual plants under fruit trees or hardy native trees, like mesquite. But if even your shade trees struggle due to the heat, you will need to put up shade cloth.

How to make a shade tunnel to protect plants from harsh desert sun:

Poor Soil

Wood mulch, wood mulch, and more wood mulch. If you want to have good soil without trucking in expensive top soil from elsewhere, or you want to preserve and replenish your precious imported dirt, you need wood mulch. As already mentioned, wood mulch holds water, keeping your plants hydrated for longer, and it shades the soil, preventing water loss through evaporation. But wood mulch also contains a lot of nutrients that slowly leach out of the chips as it rains (or is irrigated), acting as a slow-release fertilizer, and it eventually breaks down into a loose, rich soil. After just a year on the ground, you can find at least an inch of good top soil under your mulch. The longer you continue to mulch, the deeper the topsoil will go.

Layer mulch on thick (3” deep) in desert climates to retain water and protect the soil from the baking sun and blasting winds.

What To Grow

Want to know what will do well in your desert climate? Here’s a video on perennials that can survive desert temps:

And a video on fruit trees that do well in a desert environment:

Putting It All Together

Geoff Lawton is one of the preeminent experts on permaculture farming. He has a large farm in Australia in a relatively normal, temperate climate, but he also has the “Greening the Desert” project in Jordan where he is growing in a desert climate and in what has to be some of the worst dirt in the world. Martian soil looks more hospitable than what is available in his part of Jordan. But he’s managed to establish a nice homestead garden and teach others in the area to do the same.

Geoff’s technique in Jordan includes the zai pits. Jordan receives a modest amount of rain, but almost all of it falls in the wintertime, leaving their summers dry and scorching. The zai pits, swales, and rock terraces all combine to keep as much water as possible on the property so that when the dry season begins, the larger perennial plants have moist soil deep underground that they can tap. Graywater from the institute is filtered in reed beds and used with drip irrigation to provide a light watering to shallow-rooted annuals which are sheltered from the sun and hot winds by fruit trees.

The first trees that were planted on the property, however, were native trees and trees from Australia’s Outback that were planted solely because they grow fast, create shade, and produce nitrogen-rich leaves. These trees were routinely pruned and their limbs and leaves put into zai pits to create the beginnings of soil. Fruit trees were then planted in these pits, sheltered by the larger native trees. Over time, the fruit trees grew big enough that they no longer needed shelter, and the pioneering trees were removed (and mulched, of course) to make room for the growing fruit trees.

Chickens are also an important part of the equation. All food waste generated by the institute is fed to chickens, and what they don’t eat is mixed in with other plant waste from the site, plus their droppings, and after a few weeks of processing, they are left with a rich compost that can be put on all of their plants.

Abla, who lives across the road from Geoff’s permaculture institute in Jordan, is a graduate of his program and she’s turned her patch of rocky sand into a garden that’s capable of providing her with fresh food to eat and enough to sell as a decent side hustle. You can see what her homestead looks like fairly early in the process and what it looks like after 5 years of work and growth.

Abla’s original garden:

Abla’s garden 5 years later:

This couple in Arizona found that the soil under their native mesquite trees was great for their garden, so they simply dug it up and moved it to where they wanted their garden. (This is really just the natural version of Geoff Lawton’s project.)

One thing they don’t have that Geoff’s gardens in the desert have are shade trees over the garden. But it sounds like the temperatures fluctuate quite a bit in the summertime for them, and they even get a lot of rain at certain times, so it may be that they don’t need the shade on their plants as much as people in other parts of the desert (even in other parts of the same state) might need.

This retired man’s homestead is in the high desert of Colorado. Something unique he has is a hedgerow around his property to protect it. The hedgerow is full of large bushes and small trees—most (maybe all) of which are edible or medicinal. It is so dense and high, it keeps out pests, like deer, provides shelter for beneficial insects, and it acts as much-needed windbreak, keeping high winds off his more tender garden plants.

The thing about growing in a harsh environment is that you’re going to attract animals that want to eat from your garden as much as you do. My mother lives on the side of a mountain and she has a terrible time protecting her garden from deer, moles, and chipmunks because her garden is quite a feast among the rocks. I daresay a garden in a desert would likewise attract a lot of pests looking for an easy meal. (I noticed several desert gardeners using netting to protect plants from birds.) So a dense hedgerow of thorny plants, like blackberries and raspberries, or native cactus or thorny trees, to act like a fence around your property may be necessary.

This gentlemen in Colorado is growing several different kinds of grains on his 3/4ths of an acre, demonstrating that you don’t need a huge amount of land to grow enough grains to make it worth your while. He gets about 95% of his food from this one garden, plus produces all of his own seed.

Speaking of seeds, something he mentions that’s a real upside to saving your own seed from heirloom (non-hybrid) plants is that you will end up saving the seed only from plants that survive and do well in your soil and climate. Over time, your returns will get better and better as your plants adapt over the generations.

This lady and her late husband started a forest in the desert of Baja California, Mexico, where they get just 1.6” of rain, on average, per year. But they carefully selected drought-resistant trees from around the world to populate their forest. While they don’t keep this as a food forest, many of their trees have edible fruits, leaves, and/or roots, demonstrating how you can get double duty out of any shade trees you plant to protect more delicate plants.

This is the inspiring story of a Chinese woman who transformed a desert into a forest and useable farmland. It shows what’s possible with consistent effort applied over a long enough timeline. Whatever your land’s situation, it’s possible that you, too, could transform it from barren wasteland into a productive desert oasis.

Need more gardening tips? Try this page: Growing Resilience: Victory Gardens for Everyone